A (mostly) young lawyer’s thoughts on trouble in the legal profession…

Spoiler Alert — today’s post is slightly off-topic….

Like all of my fellow law bloggers–or blawgers but I refuse to use that term–I am not only the author of a lawyer blog, I am a lawyer blog fan. I have therefore followed with interest the blogs discussing law schools, new law school graduates, the employment prospects of new lawyers, the growth and contraction of the mega-firm world, and general discontent of new lawyers with life and (seemingly) everything else. The question has been asked repeatedly on some of these blogs if law school is “worth it,” and various economic tests have been devised to find an answer.

Some commentators have spent a great deal of time discussing the miseries and woes of newly-minted lawyers; indeed, AboveTheLaw.com, seems to have been founded by young lawyers specifically to discuss the woes of newly minted lawyers. Law professors–always in search of something to write about–have wandered into the field, and have done some very sobering analyses of the facts of life for newly minted lawyers who want to buy a house as just one example.

When law professors and folks publishing on-line lawyer magazines and blogs talk about trouble in the legal profession that is one thing. As Michael Gambon says to Daniel Craig in the movie Layer Cake–when Craig’s character learns that his idol in the criminal underworld has for many years been a police informant: How did you think these people make a living?

But when noteworthy law bloggers like Steven Harper, who have real legal careers start retiring from big law firms to write full-time about lawyer reform, well, that’s another thing entirely. I have touched upon topics like law firm economics and qui tam history before in this blog, but today’s post is a little different.

Suprise young lawyers — making a living as a lawyer always has been, and always will be, tough

Some of the criticism offered by the above sources (and by other sources) is on-point. Some of it is not. All of it is worth reading, for reasons I may or may not get around to explaining in later posts. But what I want to talk about today–because I am afraid at least some members of Generations X and Y may not know this–is the fact that it always has been, and always will be, damn hard to make a living as a lawyer.

Lets start with that most important of all figures to legal education–OWHJ, or Oliver Wendell Holmes Jr. Most of us heard about him while we were applying to law school, and 100% of us heard his name on the first day of law school. OWHJ had by any measure a towering intellect. He used a word where the rest of us use a sentence. He thought in paragraphs. His judicial writings rise above the normal fodder of lawyers and are in fact nothing less than English prose. His public speeches on everything from the Civil War to the meaning of life are worth reading and re-reading.

But he was a miserable failure in the practice of law; and in fact he failed to make enough money to support himself.

From 1866 (when he was admitted to the Massachusetts Bar) to 1882 (when he accepted a position at Harvard Law School) Holmes struggled to make a living. Law Professor James Chen made headlines with his formula for calculating how much money new lawyers would need to make to payoff their loans and buy a house, but home ownership didn’t become difficult for young lawyers recently, because OWHJ lived with his parents until they died.

And yes, he was married, to one Fanny Bowditch Dixwell. And yes, Mrs. OWHJ was very unhappy that her husband didn’t make enough to buy thier own house. But don’t take my word for it, just read Yankee from Olympus. That book is also important for another reason relevant to this post. Yankee from Olympus captures–and very well in my opinion–a snapshot of the Holmes family in all of their historical grandeur. You see, OWHJ wasn’t just a great legal mind, he was a bona fide product of the Boston upper classes.

When OWHJ was a small child Henry Wadsworth Longfellow read to him; at age seven he had a first-row seat at the funeral of John Quincy Adams, the Sixth President of the United States. All three of his names–that is, Oliver, Wendell and Holmes–were given to him to make sure that everyone would know that he was part of not one but three privileged families.

In short, the family history of Oliver Wendell Holmes was nothing short of the history of Massachusetts.

So yes, to say he was well-connected doesn’t quite do it–this guy knew everyone who was anyone. So if he couldn’t bring in enough clients to pay the bills, how are any of the rest of us supposed to make it?

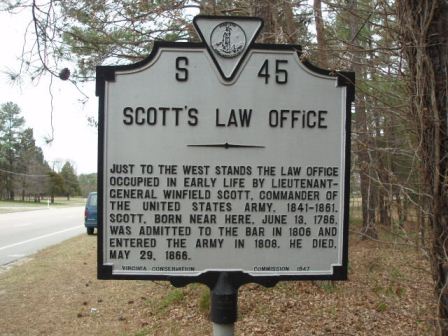

He was not the only one. In Southwest Virginia, near my great-grandfather’s ancestral home, one can find this Virginia Historical Marker:

That’s right, Winfield Scott–whose impression on the United States Army can still be seen to this day, and is rivaled only by George Marshall–started out as a lawyer. When he couldn’t make a living in private practice, he changed careers and joined the United States Army.

In fact, I think the sign says it all–“Just to the West Stands the Law Office Occupied in Early Life by Lt. Gen. Winfield Scott. Admitted to the Bar in 1806; joined the Army in 1808.”

And these are just two of the noteworthy people who were unable to make a living as lawyers–how many non-noteworthy lawyers failed to cut it in the practice of law in history? More than a few I assure you. How many political careers were launched by the inability to make a living as a lawyer? More than a few.

In those days, of course, you didn’t need a six-figure debt to get a law license, you didn’t even need an apprenticeship, although it was better to have one under your belt. Certainly the need for an expensive and lengthy education serves as a “barrier to entry” to the practice of law, and that of course is by design. You see, back in the 19th century–when the practice of law was still open to any snake-oil salesman with a distaste for physical labor–the market for legal services wasn’t less crowded that it is today, it was more crowded.

So lawyers did what every other group of tradesmen did in the 19th century when their livelihood was threatened–they closed ranks and organized to protect their own. This is according to Lawrence Freidman.

The moral to the story is this–and it is sometimes said to be the oldest wisdom in the book. There ain’t no such thing as a free lunch. Are there too many law schools? Yes, there certainly are, but I am betting we will see as many as one-third fewer law schools ten years from now. Do law schools charge too much for tuition nowadays? Yes, they certainly do. But they charge what the market will support; otherwise they would be out of business, and therefore the question becomes a more fundamental question about the nature of our economy and about the fundamental human desire to make money and become famous.

Simply put, I think that much of the discontent among young lawyers is because they think it is an automatic given that everything should be handed to them. They want to dial it in, so to speak, and make tons of money. They just don’t understand that to make a good living in a profession, a person has to become the right blend of artist and businessperson. Too much of one or the other and you are in trouble. And you most definitely can’t dial it in–it takes constant effort and constant attention.

Perhaps most important, to make it as a lawyer, you absolutely positively MUST be a self-starter. There is no room in this profession for someone who wants everything handed to them…

I offer no opinion on whether a “young person” should go into law as a career, but I can say this–I am glad I chose to become a lawyer. Moreover, what is happening with the legal profession is not limited to the legal profession, as many commentators from other sectors of the economy point out. If anyone really, really wants to get at the bottom of what is going in the legal profession–and elsewhere in our economy–I think a must-read book is Tyler Cowen’s The Great Stagnation. It’s a short book but an important one for those of us interested in where things are headed.